A journey through Albania’s breathtaking nature and the challenges facing its tourism.

By Esmeralda Topi and Atdhe Mulla

The morning of August 25 found us on the road. Departing from Tirana, we headed south to get a firsthand look at a tourist season that started with high expectations but never materialized into the much-talked-about “boom.”

The drive to Himara took roughly three and a half hours. Fortunately, leaving early spared us from traffic, even on the Tirana–Durrës highway, which has become a travel nightmare in recent months due to ongoing roadworks.

At the entrance to Vlora, near the roundabout known as “Kulaçi,” a few raindrops briefly dampened our mood. But as we approached “Uji i Ftohtë”, the sun reappeared. The beaches along Vlora’s promenade were nearly empty, with only a handful of sunbathers scattered along the sand.

In Radhima, the sun blazed as if it were mid-July, yet even here, there weren’t many people around. The view along the road strengthened the sense that Albania was not experiencing a tourist boom this year. Official data confirmed this impression. According to INSTAT, in July, the peak of the summer season, the number of foreign tourists increased by only 0.4 percent, while total visitors rose by 1.5 percent compared to the previous year, a barely noticeable change.

From Llogara to Himara

On the way to the Llogara tunnel, a blue sign made us laugh in the car: Green Coast 13 km, Mykonos 598 km, Bodrum 773 km, Ibiza 1,531 km.

I joked to the group:

“All of these places have one thing in common, sky-high prices.”

A few minutes later, after passing through the still toll-free tunnel, we found ourselves above Palasa. The view of the Ionian Sea was breathtaking and accompanied us all the way to Himara, our final destination. Unlike Vlorë, Himara was vibrant. The beaches were filled with people, locals and foreigners alike, giving the town a completely different energy.

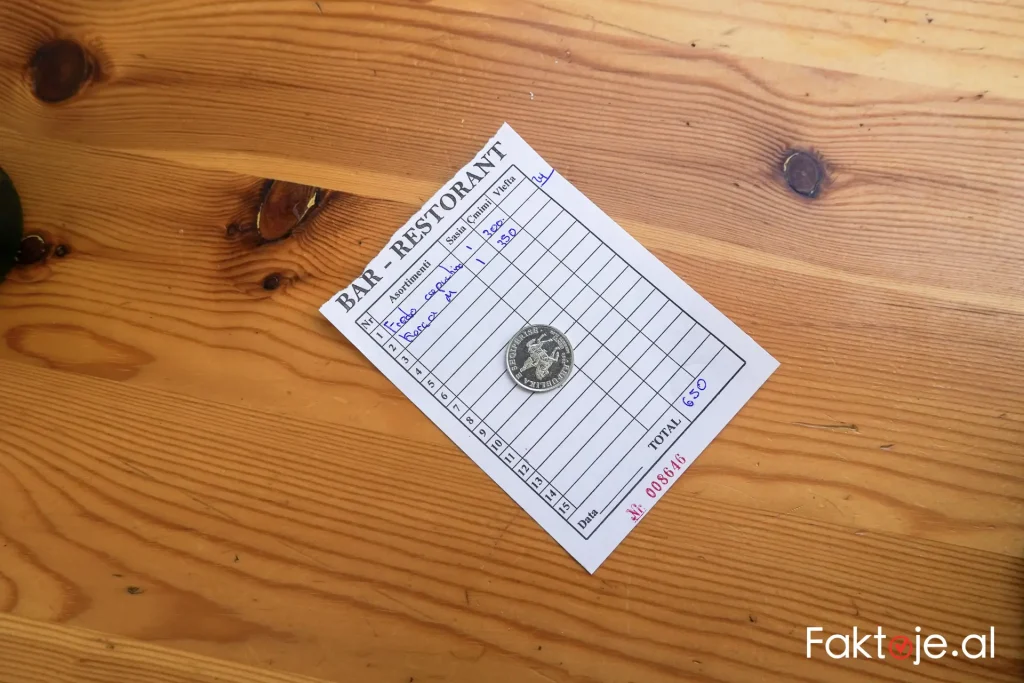

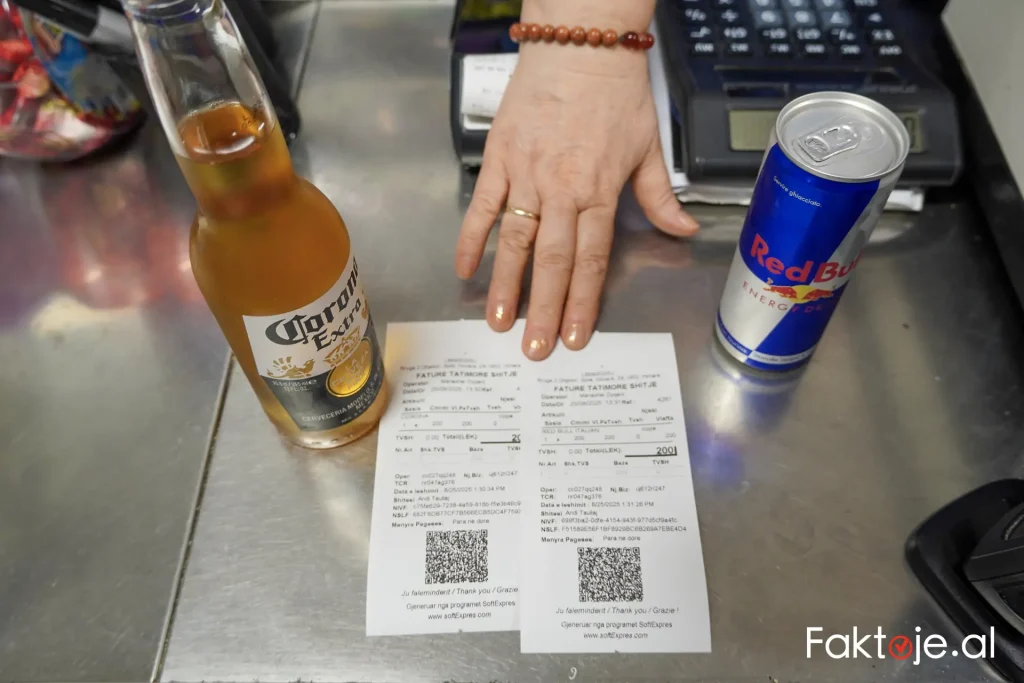

We settled at a modest café by the public beach. The order was simple: a beer and an iced coffee. The price? 650 Lek. Nothing unusual up to that point, but when I asked for the receipt, the waiter, a polite young man, seemed uncomfortable. “We haven’t started it yet…” he said, clearly embarrassed.

I insisted, and after a short while, he handed me a handwritten slip. It immediately brought to mind the famous scene of the oregano bill that Muçi asked Bardha for.

Himara is not Dhërmi

In Himara, prices vary widely. A night in hotels ranged from 5,000 to 50,000 Lek, while an umbrella with two sunbeds cost between 1,000 and 2,000 Lek. Restaurants along the promenade had prices similar to those in Tirana, far from the “phantom bills” that circulate on social media. The locals were clear and insistent

“Himara is not Dhërmi!”

Still, they admitted that this year had a clear downturn.

In a small market, I purchased a bottle of water for 50 Lek With a receipt. Noticing my astonishment, the owner joked, “Look at all the prices… they’re the same as in Tirana. You’re not in Dhërmi here!

“The hotel is full, but the restaurant isn’t seeing the same business as last year. There’s a decrease of at least 20 percent,” said the manager of a hotel in Potam.

Albanians dependent on “sponsors”

Local holidaymakers complained about unaffordable prices. A retiree from Elbasan, vacationing with his family in Potam, joked:

“For Albanians, it’s very expensive. I came with a sponsor because I couldn’t afford it myself. Who’s the sponsor? My brother-in-law!” and he laughed heartily.

Foreign tourists shared a similar opinion. A Spanish woman, spending two weeks traveling from the north to the south, described Albania’s prices as “roughly like in Spain.”

“Not very cheap for us; it’s a country to discover. Prices are similar to those in Spain,” she said, while emphasizing that Albania is still a place worth recommending.

Two American girls, on the first day of their vacation, had a different perspective.

“This is our first time in Albania. We saw it on TikTok and Instagram. We’re traveling the world searching for affordable experiences, and Albania was on our Balkan list. After doing some research, Albania seemed very cheap and beautiful.”

The girls had come to Albania after spending a week in the Baltic and Scandinavian countries.

“Compared to those countries, which were quite expensive, it’s cheaper here. Even compared to the U.S.,” they said in unison.

Tourism is like olive trees

In the courtyard of a family-run hotel in Himara, under the shade of olive trees, I met the Neranxi brothers along with their mother. For 20 years, they had been running the “George” hotel. Arturi, the eldest brother, views tourism as a long-term commitment.

“I personally maintain the same standards, but I give it my heart and soul. I don’t see it as taking the money and leaving; I invest in the client so they leave with a good impression and, if they return to Himara, they will definitely come back here.” His brother added a fitting analogy.

“Tourism is like olive trees, some years they bear fruit, other years they don’t. It’s the same with tourism because people keep moving.”

They argue that this year’s decline in tourism isn’t due to high prices in the south. Rather, they believe that Albania has become generally more expensive.

“Life in Albania has become more expensive,” Turi points out.

This seemed true as I spoke with them, dedicated family members committed to an industry that, as they acknowledged, is still in its infancy.

“The issues we face in the tourism sector were here last year and will continue next year. We are at the beginning of mass tourism; we lack experience and a tourism tradition like our neighbors have,” Arturi continued, also admitting to the abuses that occur in the south.

“If a room offers conditions for 70 Euros, there’s no reason to sell it for 90 just because everyone else does. That’s where the abuse happens,” he added.

In the end, Arturi stresses that Albania’s tourism industry should focus on local visitors.

“My advice is to invest in Albanians, including those from Kosovo and the diaspora. Albanian tourists have a unique trait that few recognize they are the only ones who might visit twice in one season. Even three times.”

Kosovo is no longer a “guarantee”

Zak Topuzi, head of the “Albanian Tourism Association,” recalls that Kosovo was for years the main source of tourists. But now, he says, “Kosovo is no longer a guaranteed market. Freedom of movement has given people freedom of choice, and Kosovars are often choosing Greece for the best experience.”

“A key factor influencing this shift is the competitive power of regional tourism offers priced in euros. The euro’s devaluation by 27% (compared to the Lek) has sharply increased the cost of Albanian packages. In Greece, for the same price, a Kosovar family can access standardized services, well-organized resorts, villas with limited capacity, and guaranteed privacy,” Topuzi explains.

Economist Artan Gjergji adds that the ‘grab whatever you can’ mentality is unsustainable.

“The market is unforgiving. There is no greater penalty for a business than a shift in client behavior and preferences caused by abuse. Reflection on mindset is necessary before it’s too late.”

He also points out that prices often rise not directly in nominal terms but indirectly, by exploiting product quantities.

“A medium pizza is sold at the price of a family pizza, while a smaller pizza is offered as standard. Similarly, the portion of a 270 Lek souvlaki in Tirana equals two 350 Lek souvlaki in Shëngjin, Durrës, or even worse in Vlora and Saranda.”

Irena Beqiraj, an expert in economics and finance, views the issue from an economic perspective.

“Tourism relies on infrastructure that is used only in the summer. Investments utilized for just three months a year create heavy pressure on prices. Additionally, Albania imports most of its products, and this model inevitably leads to inflation.”

***

The drive back from Himara left us with a single thought: Albania is blessed in natural beauty, but tourism cannot rely on sun and sea alone. It demands respect for visitors, foresight for the future, and a vision that extends beyond the summer season.

Simply opening the doors isn’t enough if you don’t know how to keep your guests coming back.