Four years ago, a political ‘agreement’ was reached for a comprehensive electoral reform. However, the 12-point agreement was breached from the outset, and today it appears quite idealistic to be implemented. As the depoliticization of the electoral administration and the voting rights of expatriates remain unresolved, the discourse has shifted towards the internal conflict within the fragmented Democratic Party (PD), hindering the possibility of constructive dialogue and consensus on electoral reform. If the general elections take place in spring 2025, the available time for reaching consensus on electoral reform may prove insufficient, potentially leading to a vicious cycle of discord for the country.

Esiona Konomi

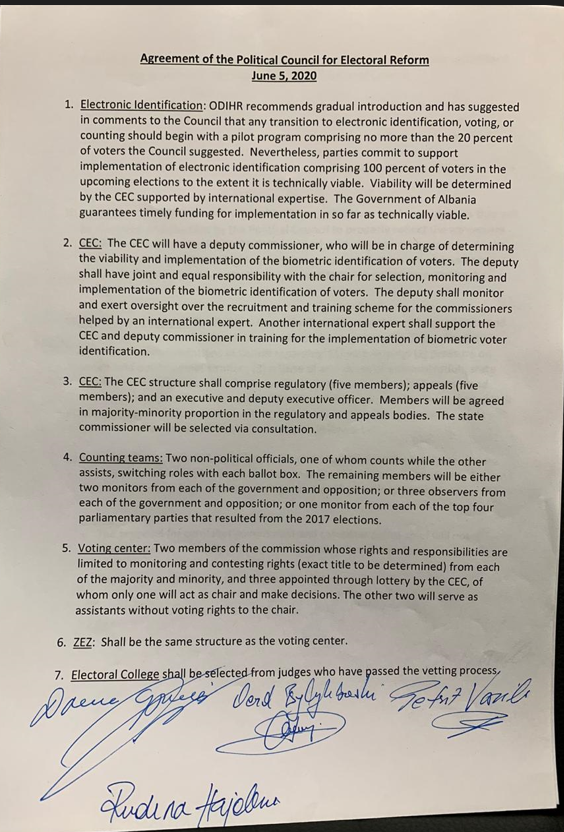

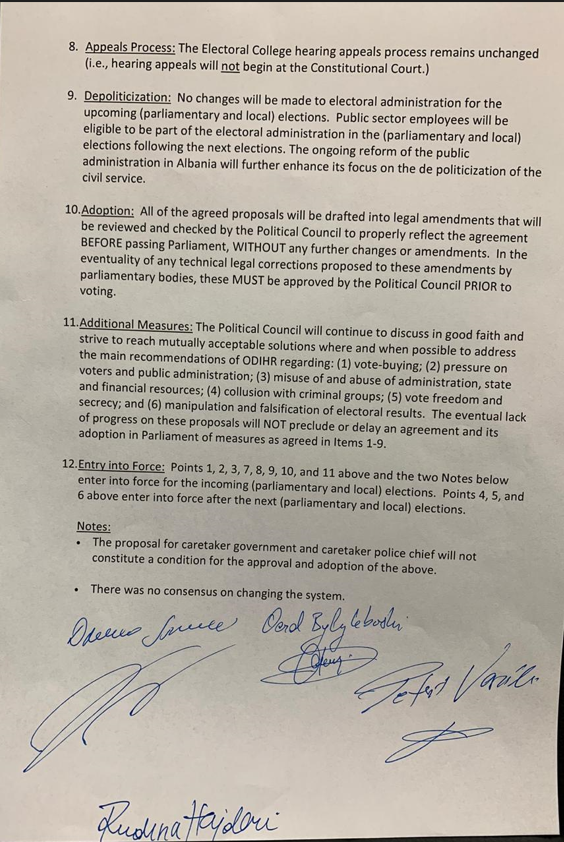

On the late evening of June 5, 2020, Ambassadors Yuri Kim and Luigi Soreca applauded the signing of an agreement at the Political Council for electoral reform.

The USA and the EU had thus concluded over 5 months of negotiations, led by them in an extra-parliamentary format. This format brought together the Socialist Party represented by Damian Gjiknuri, the new parliamentary opposition represented by Rudina Hajdari, and the opposition that had nullified their mandates in the Parliament, represented by Oerd Bylykbashi for the Democratic Party (PD) and Petrit Vasili for the Socialist Movement for Integration (LSI) (now the Party of Freedom).

The Political Council served as a ‘diplomatic formula’ to break the political deadlock and enact a comprehensive accepted electoral reform, involving even those actors outside the institutions who represented a significant political reality.

The 12-point agreement of the Political Council, signed on June 5, 2020.

4 years later, the same embassies are once again calling for the same thing: a comprehensive electoral reform. The institutional situation is similarly complex, if not more so than four years ago, but with a different aspect. At the forefront of this task, Damian Gjiknuri continues to lead for the Socialist Party, while Enkelejd Alibeaj represents the opposition. But, the latter only enjoys the support of a small group within the parliamentary minority. More than 40 opposition deputies are calling for Oerd Bylykbashi to assume that position.

It is not possible for colleagues to act as if they still have our trust. We gave them our trust, now it’s gone. It’s unacceptable for 7 deputies to bear the weight of opposition representation, and not us, who are around 50 deputies‘- stated Gazment Bardhi in the Parliament on Friday, January 19.

Recently, the parties have resumed discussions on electoral reform, but its progress is hindered by the internal conflict within the Democratic Party and the majority’s approach to this crisis.

‘The opposition’s cockfight is not about voting in the reform commission! It is a battle between them as to who will administer the right of veto enjoyed by the co-chairs of the Commission. We will attend the meeting whenever Alibeaj calls for it. Physically!’ – said the socialist member of this committee, Toni Gogu.

Tearing up of the 2020 agreement

Despite the considerable excitement it generated, the agreement signed almost 4 years ago by Gjiknuri, Bylykbashi, Hajdari, and Vasili was not substantially implemented.

In our fact-checking at Faktoje, we scrutinized the 12 points outlined in the 2020 agreement. The findings indicate that only 2 of them have been implemented: specifically, the agreements regarding the use of technology in elections and the restructuring of the Central Election Commission (KQZ).

Conversely, both parties have violated their initial commitment not to amend electoral rules ‘without prior approval from the Political Council.’ They have failed to integrate the agreement aimed at depoliticizing the electoral administration. Additionally, contrary to the commitment made in the jointly signed document, the Political Council did not convene beyond that specified timeframe.

The depoliticization of the electoral administration

The depoliticization of the electoral administration, meaning that the election officials and commissioners are no longer appointed by political parties, is an early recommendation of the OSCE-ODIHR and a declared priority of the Socialist Party.

‘The fact that it hasn’t been done in 30 years doesn’t imply that we shouldn’t do it now,’ stated the Chairman of the Socialist Party, Edi Rama, on June 4, 2020, just a day before the signing of the political pact.

In the agreement of June 5, 2020, this was one of the most difficult points to negotiate. After numerous negotiations, the Socialist Party withdrew the mentioned request, reaching an agreement with the opposition for the application of this formula in the 2025 elections.

The formula signed in the agreement, specifically in points 4 and 5, was as follows:

‘4. Counting Groups: Two non-political official teams, with one counting and the other assisting, alternating roles at each ballot box. The other members will either consist of two monitors, one from the ruling party and the other from the opposition, or one monitor from each of the four major parliamentary parties from the 2017 elections.

‘5. Voting Centers: Two commission members with restricted monitoring rights and responsibilities, one from the ruling party and one from the opposition, and three appointed by lottery by the CEC, of which only one will serve as the chair and make decisions. The remaining two will serve as assistants without voting rights.

In the last point of the 12-point agreement, written in English only, it was stipulated that these formulas would not be applicable to the upcoming parliamentary and local elections (2021, 2023) and would come into effect for the 2025 elections.

Although four years have passed since that agreement, the parties have never presented any legislation in the Parliament, whether comprehensive or partial, to implement this formula.

The amendments to the Electoral Code immediately following this agreement did not incorporate these points, with the possibility of coming into effect in 2025.

From June 2020 until now, five proposals to amend the Electoral Code have been submitted in the Parliament, yet none of them reflects the agreement reached in the Political Council.

The requests for amending the Electoral Code submitted to the Parliament

The Central Election Commission, referring to ODIHR recommendations, considers that the administration of elections at lower and intermediate levels by specifically appointed or solely politically selected electoral administrators ‘has jeopardized the technical standard’ of preparation and conduct of the electoral processes, as well as the public trust in them.

‘The CEC appreciates the positive consideration of this recommendation, as it removes, at least partially, the absolute right of parties to appoint electoral administrators at the secondary and tertiary levels of administration. According to Ilirjan Celibashi, the State Election Commissioner, this would contribute to the establishment of a professional, well-trained, and integrity-focused body of administrators,’ – stated Celibashi for Faktoje.

‘The June 5th assassination’

The comprehensive agreement also includes a point with the aim of ‘reconciliation’ among the four parties, emphasizing that they would not ‘betray’ this agreement.

At point 10, it states:

‘Adjustment: For all the agreed-upon proposals, legal amendments shall be drafted, subject to reassessment and scrutiny by the Political Council, ensuring they reflect the agreement BEFORE it moves to Parliament and WITHOUT any additional changes or amendments. In case of technical corrections, they shall be approved by the Political Council BEFORE the vote takes place.

This paragraph was partially implemented on July 21, 2020. The Electoral Code incorporated the agreement, but 9 days later, the Socialists, in agreement only with the ‘new opposition,’ without consensus with the PD and LSI, had relinquished their mandates. They amended the Constitution, opening the lists, where citizens were given the right to vote for both the party and a preferred candidate within the party’s list. The new movement also altered the coalition formula, a change to which PD and LSI did not agree and were not part of the dialogue.

‘Only Edi Rama is capable of making a deal to break another deal. He stated after June 5th, he would terminate the agreement, and indeed, he followed through on this,’ – said Oerd Bylykbashi, one of the co-signers of the breached agreement.

Screenshot of the statement by the Democratic Party (PD) deputy Oerd Bylykbashi

The Political Council was forgotten

At the end of the agreement, which had the two most important ambassadors in Albania as ‘godfathers’, the local political spectrum also agreed on ‘additional measures,’ specifically the continuation of meetings and political discussions in this comprehensive format, known as the Political Council.

’11. Additional Measures: The Political Council shall continue to engage in confident discussions and strive to find mutually acceptable solutions where and when possible to address the ODIHR’s key recommendations related to: vote buying, pressure on voters and administration, financial and material resources, misuse of administration, collaboration with criminal groups, freedom or secrecy of the vote, and manipulation and falsification of election results.

In reality, ODIHR has reemphasized these recommendations as priorities for the 2021 and 2023 elections, but the Political Council did reconvene, neither for these issues nor for others.

None of the parties has ever explicitly mentioned convening a meeting or dialogue in this format, despite the earlier commitment to continue discussions in confidence and seek solutions.

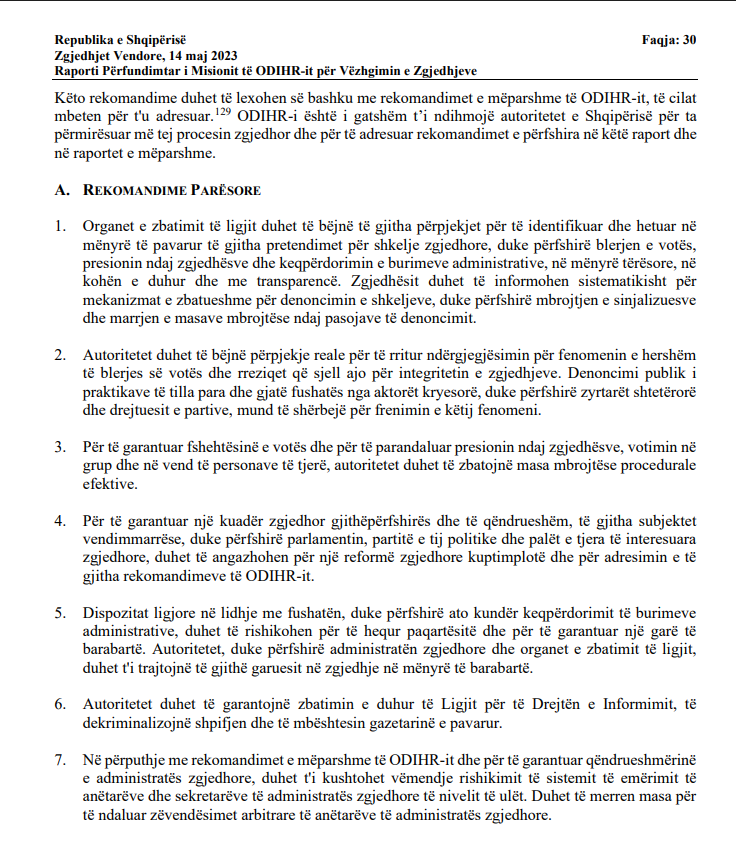

ODIHR’s recommendations for the local elections on May 14, 2023

Consequences…

As the parties have intensified efforts for electoral reform, the country is almost a year away from parliamentary elections.

The existing legal framework has issues and gaps that need to be addressed. The long-established guidelines from the universally recognized arbiter, OSCE, have not been incorporated, as noted in the organization’s latest report on the general elections in the country.

‘The legal framework requires further review to address the unaddressed recommendations of ODIHR and of Venice Commission, as well as a series of uncertainties and inconsistencies. Amendments in the law should be preceded by an open and inclusive consultation process and adopted before the upcoming elections’. (Read the FULL ODHIR recommendations HERE‘

Concerned about the delay in this reform, the State Election Commissioner, Ilirjan Celibashi, expresses his worries and reminds the parties that they need to fulfill their duties, as the upcoming elections are expected to take place between March 15 and May 15, 2025.

‘It is crucial that all possible amendments to the electoral legislation are implemented no later than one year before the date when the next elections for the Parliament of Albania could take place’, – emphasizes Ilirjan Celibashi.

Ilirjan Celibashi, Election Commissioner

Former member of the CEC, Bledar Skënderi, told ‘Faktoje’ that one year is insufficient for the CEC to be fully prepared qualitatively.

‘If new methods are to be implemented, involving public administration, teachers, or other professionals in the roles of polling station commissioners or vote counters, the CEC needs to be provided with sufficient time to take the necessary measures. This institution should have clear rules and should not be subjected to surprises that do not allow for qualitative preparation’, –argues Skënderi.

Bledar Skënderi, former CEC member

The State Election Commissioner has sent a letter to 9 leaders of parliamentary parties, reminding them that the electoral law has serious problems arising from some mandatory decisions made by the Constitutional Court, such as: the review of the formula for the distribution of the mandate known as the quotient; the vote of expatriates; depoliticization of the election administration; campaign financing; expansion of the electronic voting and counting scheme, etc.

The letter from Commissioner Celibashi sent to parliamentary parties.

Based on the conducted verification, taking into account the collected information and the opinions of electoral issues experts, we will consider the political commitment of 4 years ago to ensure comprehensive and universally accepted electoral reform, as an Unfulfilled Promise.