By Sebi Alla

The legalization of sinformal housing, a promise as old as the unauthorized constructions themselves in our country, remains hostage to political interests. Official data obtained by Faktoje.al indicate that since the legalization process began in 2006 until now, legalizations have been used as a crucial tool for political support, particularly during central and local election campaigns.

In 2013, Prime Minister Edi Rama promised not only free home legalizations but also the completion of the process within his first government term. Furthermore, Rama declared that he would take full responsibility for the progress of the legalization process. “I want this commitment, signed by me, to be placed somewhere in plain sight for everyone, so that after four years, an evaluation can be made based on this pledge,’ Rama stated at the time.

Electoral Benefits

The Socialist Party and the Democratic Party (as well as the SMI (LSI) when it was in power) have used the process of granting ownership documentation for informal housing not only as an electoral promise but also as a means to secure votes, significantly increasing the issuance of legalization permits, particularly in the four months leading up to election day.

Election expert and Head of the Election Monitoring Organization KRIIK Albania, Premto Gogo, told Faktoje that this phenomenon is widespread during campaigns, ‘influencing or even pressuring citizens to vote’ for the ruling party. ‘Unfortunately, the growing misuse of public resources and state activities to gain an electoral advantage for a political party has turned the legalization process into one of the main tools for guiding, directing, or even forcing citizens’ votes,’ Gogo stated.

As the elections approach, both central and local government leaders have openly violated the Electoral Code, which prohibits the promotion, publication, and physical distribution of property documents during election campaigns.

In June of last year, Prime Minister Edi Rama, just weeks before the partial local elections in Himara, was seen with SP candidate Vangjel Tavo, holding a significant number of ‘property certificates for homes. ‘..Today, we have 789 certificates. In the entire Vlora district, there are around 4,200 or 300, including today’s certificates, some of which we will distribute here. This physical distribution is also meant to encourage others to apply,’ Prime Minister Rama stated.

For 34 years, many of the residents of Dhërmi were unable to obtain property certificates for their homes and land, but it took a heated local election campaign (to regain control for the Socialist Party) for them to finally receive the document that had been ‘held hostage’ for three decades by the Prime Minister.

During the campaign in Himara, in at least three instances, the Prime Minister personally distributed the legalization permits for homes, while also asking residents to vote for the SP candidate, Vangjel Tavo. ‘The increase in the issuance of legalization permits in election years is the most compelling evidence that proves this phenomenon in numbers. It is now widely accepted that the use of this process for electoral advantage has become a common practice for all political forces that have appointed or led the state bodies responsible for managing the legalization process over the years,’ said Premto Gogo, head of KRIIK Albania.

Photo from Tirana

Election Years, Legalizations, and Votes

A statistical report from ASHK (State Cadastre Agency, formerly ALUIZN – I ‘the Agency for Legalization, Urbanization, and Integration of Informal Zones’) obtained by Faktoje.al shows that from 2006 to 2013, applications for the legalization of informal homes were opened twice. The total number of applications received amounted to 323,082 properties across Albania. However, after 2013, additional processes were launched, meaning that illegal constructions continued, with some even being included in the legalization process outside the official application deadlines.

It turns out that around 94,000 buildings, or 29% of the total applications, have been classified as unlegalizable, but their fate is still unclear.

‘It must be considered that due to some self-declaration campaigns, there are a number of duplicates in the self-declarations (the same building declared multiple times, ranging from 20-30% of the self-declarations). Additionally, the self-declarations include several buildings that cannot be included in the legalization process due to their construction period. This figure ranges from 7-10% of the self-declarations. Therefore, to obtain the actual number of illegal constructions, these two categories must be subtracted from the self-declarations. In conclusion, the actual number of illegal buildings included in the legalization process between 2006 and 2015 is 320,000 buildings,‘ states the report from the Albanian Cadastre presented in Parliament by the former head of this agency, Artan Lame.

After the self-declaration process and field monitoring of illegal buildings that applied for legalization, it has been found that around 94,000 buildings, or 29% of the total applications, are classified as unlegalizable. However, their fate remains unclear, as property documents have been issued for some buildings at different times, even though they are on the ‘red map’, which excludes them from legalization.

Some of the buildings were found to have been constructed in coastal areas near the sand dunes, while others were built along rivers, near collectors, drainage pumps, or in areas designated for public works, where urban planning plans had been approved before the informal buildings were constructed. These are the official data, and the only ones provided by the ASHK.

Sources from the ASHK confirmed to Faktoje that even today (2025), the figures remain consistent, with no significant changes in the numbers.

Although the legalization process involves complexities in planning, documentation, and subsequent legalization, politics has taken advantage of this phenomenon to gain votes. We are backing up the facts with official data.

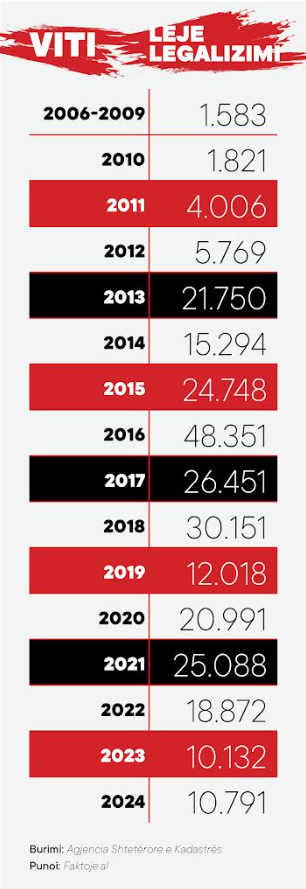

(Note: The table shows the legalization figures by year, with electoral years highlighted in colours)

Statistics

Faktoje.al analyzed the statistics for the issuance of legalization permits, showing an upward trend specifically in electoral years. Seven electoral processes, both local and central, took place between 2006 and 2024.

Legalizations and Berisha

Between 2006 and 2009, only 1,583 legalization permits were granted. In 2010, 1,821 permits were issued across the country, but the following year, coinciding with the local elections, 4,006 legalization permits were granted. In 2012, 5,769 legalization permits were issued, but the trend, which showed a slight upward slope, saw a sharp increase in 2013, corresponding to the Parliamentary General Elections, with 21,750 permits granted.

Despite the relatively low number of legalizations permits issued between 2006 and 2013, about 90% of the permits granted during Berisha’s government were issued between the two electoral campaigns, local and central, in 2011 and 2013.

Legalizations and Rama

After the political changes, the left-wing party, with Edi Rama as prime minister, came to power, and one of the main promises during the electoral campaign was the free legalization of homes. However, it turned out that only the preparation of the documentation was free, while citizens had to pay for the land and the building, with prices varying from one region to another. Full free legalization was granted only to those who had constructed their homes on their own land and had the necessary documentation, such as property or agricultural titles. But not only that. In 2013, Prime Minister Edi Rama also promised that the process of legalizing houses would be completed within the first term of the government, and that he would personally be responsible for overseeing the progress of the legalization process. ‘I want this commitment, signed by me, to be placed here, visible to everyone, and the evaluation to be made after 4 years based on this pledge.’ xxx

Figures

In 2016, the largest number of legalizations permits in all the years since the start of the process was issued, with a total of 48,351 permits distributed.

In 2014, 15,294 legalization permits were issued, and a year later, which coincided with the local elections, ALUIZN (now ASHK) distributed 24,748 permits. In 2016, a significant number of legalization permits was granted, totaling 48,351 permits, the highest ever since the process began.

The majority of these permits were issued during the last three months of 2016, or six months before the general parliamentary elections. It was the year when ALUIZN was led by LSI (SMI). The large influx of legalization was accompanied by numerous abuses. A series of arrests and legal actions were taken against the directors of ALUIZN in the regions, as well as specialists from this institution, including those from the Cadastres, during 2016, 2017, and 2018. Most of the abuses involved commercial properties such as service units, hotels, or even apartments that had been classified as illegal during the first verification phase.

Until 2021, the legalization process involved two institutions: ALUIZN, which issued the permits, and the Cadastres, which registered the documentation and provided citizens with property certificates.

Meanwhile, in 2017, the year corresponding to the general parliamentary elections, 26,451 legalization permits were issued. In 2018, there was another increase, with 30,151 permits granted. However, 2019 stands out as an exception, and there seems to be a reason for this. In 2019, only 12,018 legalization permits were issued nationwide. Despite being an electoral year, as the local elections took place in June, the number of legalization permits was very low. The fact is that the ruling majority had already secured its victory, as the opposition boycotted the elections, and all 61 municipalities were won by the majority, effectively turning the elections into a mere official formality.

ASHK (State Cadastre Agency)

However, ASHK’s report on historical indicators offers another explanation for the sharp decline in the number of permits issued in 2019. ‘The significant reduction in the number of legalizations in 2019 occurred due to the approval in January of that year of an amendment to the Local Tax Law, which conditioned legalization on the prior payment of the infrastructure impact tax,’ the response states.

In 2020, 20,991 permits were issued. The following year, which coincided with the general parliamentary elections, 25,088 legalization permits were granted. The curve dropped significantly a year after the elections. For 2022, the State Cadastre Agency issued 18,872 legalization permits. This downward trend continued into 2023 with 10,132 legalization permits, while in 2024, 10,791 permits were issued, with the majority of them distributed in the last three months of the year.

Crime without punishment

The law clearly defines that every public servant, in carrying out their duties, must be impartial and strictly adhere to the law, both in letter and spirit. Misuse of a public office by exploiting one’s position and state activity for the benefit or favor of a political or electoral entity constitutes a clear violation of the law, not only electoral but also criminal law. ‘In the case of property certificates or legalization permits, the law strictly prohibits officials, in the exercise of their duties, from offering the service that belongs to the citizen in exchange for making any request against their will to participate in the electoral activities of an electoral entity, whether or not they participate in the elections, support or not a political party or candidate, or vote in a particular way. This violation is addressed by criminal law (Article 328/a of the Penal Code), which imposes imprisonment on the offender for one to three years,’ says electoral affairs expert, Premto Gogo.

According to him, it is acknowledged that there are situations where this service is provided by favoring the citizen in a manner that is against the law. This is in exchange for the citizen’s commitment to sign in support of a candidate in the elections, vote in a particular way, or engage in illegal activities to support a candidate or political party. (Passive corruption in elections, for which the offender faces imprisonment from one to five years).

‘This case is difficult to prove and report to the appropriate judicial authorities, as criminal law in such a situation has legal consequences for both parties, the official and the citizen. It is precisely this particular case, where the law is violated by both parties, that is deliberately misrepresented as if it aligns with the law, even in the first instance, when the citizen is entitled to receive the legalization permit and property certificate in a regular and correct manner, which is not the case,’ says Gogo.

Electoral Code

If we were to address the electoral period, the Electoral Code and Decision 9/2020 from the Regulatory Commission clearly define the obligation to prevent the misuse of authority and state functions to gain electoral advantage for any political subject or candidate. This means that state officials must not, under any circumstances, condition or create benefits for electoral purposes in exchange for fulfilling their duty to provide the requested service to citizens, including the legalization permit and property certificates. It is important to note that, even though the country is in an electoral period, the continuation of the normal work by the relevant state institutions to issue citizens the appropriate property certificates is completely natural, as long as all procedures and criteria outlined by the law are followed.

In the photo: Premto Gogo, Head of KRIIK ALBANIA

‘What is prohibited during this period in relation to this process is the issuance of these certificates to citizens in public activities, which means in an event where citizens or other officials, media, etc., are invited. A public activity that is not allowed includes cases where the property certificate of a citizen is collected personally, but the activity is visually documented with photos or videos and shared in the media or on social networks, with the intention of informing the public about it,’ says Gogo.

Violation

Although the law is clear, the issuance of legalization permits or property certificates for buildings constructed before 1990 by political leaders, the prime minister, ministers, local officials, or ASHK managers became routine, especially during the electoral campaigns of 2015, 2017, and 2021.

The distribution of legalization permits and property certificates for buildings constructed before 1990 by political leaders, including the Prime Minister, ministers, local leaders, and ASHK officials, had become a common practice, particularly during electoral campaigns in 2015, 2017, and 2021.

Problematic Areas

One of the areas where the distribution of legalization permits was notably used was in the Ish Këneta area in Durrës. ‘I am confident that, together with the Mayor in office now and after the elections, just as we have improved the infrastructure in this area, we will turn the Këneta area into a neighborhood that truly deserves to be called New Durrës,’ said Prime Minister Edi Rama in April 2015, standing alongside his candidate for the Municipality of Durrës, Vangjush Dako. Dako, who was distributing legalization permits alongside Rama at the event, stated: ‘I am very happy that, after two years of promises in this area, we are here today to distribute 1001 permits.’ A few weeks later, Prime Minister Rama acknowledged that ‘perhaps it was a mistake’ to distribute the legalization permits during the campaign period, but the ‘ritual’ of distributing property documents before and during election campaigns continued.

‘The prohibition set forth in the Electoral Code ensures the principle of equality in elections, preventing any benefit or advantage from being granted to the ruling political party or the one associated with the head of the institution. As a result, all perceived advantages, particularly in the process of obtaining the property certificate, are solely attributed to the state institution’s obligation to serve citizens accurately, promptly, and in full compliance with legal procedures,’ explains Gogo.

In the picture: Area of Ish-Këneta

Central Election Commission (KQZ)

In cases where violations are proven through the administrative investigation conducted by the CEC, sanctions are applied according to Article 171 of the Electoral Code. These sanctions include fines ranging from 3,000 to 90,000 LEK (Albanian Lek) for individuals assigned with duties under the electoral law, or fines between 1,000 and 2,500 LEK for other violations of the electoral law that are not explicitly foreseen.

‘Specific cases of abuse of state authority for electoral purposes that have been made public can be mentioned, such as the case of the distribution of property certificates in the 5 Maji neighborhood by the Mayor of Tirana, Mr. Erion Veliaj, on January 18, 2025; the distribution of property certificates in Himara before and after the August 4, 2024 elections by the former Prefect of Vlora and now Mayor of Himara, Mr. Vangjel Tavo, along with Prime Minister Edi Rama and other political representatives from the Socialist Party; the distribution of property certificates to residents of Gosa and Spille in Kavaja on January 13, 2023, by the Director of the Albanian Cadastre Agency, Artan Lame; and the distribution of legalization permits for residents of the Hysgjokaj administrative unit in Lushnja on December 28 and 30, 2020, by Socialist Party MP Bujar Çela, among others,’ says Gogo.

These matters have been referred to as violations of the Electoral Code, but when it comes to its enforcement and the administrative measures that should be taken by the CEC and KAS, practice has shown that a clash has arisen between the institutions responsible for election management.

KAS

According to the Electoral Code, KAS is the competent authority for reviewing administrative appeals and imposing sanctions for violations of electoral law. ‘The lack of effective interaction between the three governing bodies in the Central Election Commission, namely the State Election Commissioner, the Regulatory Commission, and the Appeals and Sanctions Commission, has led to increased divergences and differing interpretations of the legal framework. This has consequently weakened the enforcement of the law and created unnecessary complications and problematic precedents in decision-making,’ states the head of KRIIK Albania.

Ambiguity

The ambiguity in the approach and decision-making of the CEC bodies concerning the abuse of public office and state resources has led to the continuation of illegal activities by public officials. This includes the legalization process and the issuance of property certificates. The situation is also due to the lack of official information on the internal operations of these institutions, as well as the absence of reports regarding the illegal procedures followed by them.

Unfinished process

In June 2024, Prime Minister Edi Rama emphasized the need to accelerate the legalization process, describing it as a priority for municipalities. However, in November 2024, Faktoje reported that the new role of municipalities in this process had begun with missed deadlines.

Over the years, developments have shown that despite advances, and the parallel benefits for the major political parties during election periods, the legalization process remains incomplete, even though it has been underway for 19 years.

Thousands of citizens are still waiting for legalization permits, while also anticipating election campaigns to obtain property documents for their homes, lands, or arable lands, because time and facts have shown that this is precisely the period when there is a ‘relaxation’. Therefore, Prime Minister Edi Rama’s promise to finalize the legalization process within the first term should be considered unfulfilled.