Esmeralda Topi

In August 2019, a photo shared by the satirical page “Brryli Broadway” sparked a heated discussion on social media. It showed Prime Minister Edi Rama sitting in a restaurant on Vlora’s Lungomare, holding a lit cigarette.

The Prime Minister was violating the anti-smoking law, which had been enforced with great publicity in the summer of 2014 and further tightened five years later.

Rama denied breaking the law, arguing that he was in the outdoor area of the restaurant. However, details in the photo revealed otherwise. Commenters noticed that the wine bottles in the background were stored on shelves, a setup that only occurs indoors, especially during the peak of the sweltering August heat.

“In which restaurants is wine kept outside when the temperature reaches 40 degrees? In none,” wrote one citizen.

This was not an isolated case. Over five years, the new anti-smoking law began to show the first signs of failure. One of the most important public health laws gradually became a formal rule, largely ignored by everyone.

From strict enforcement to state indifference

When the new anti-smoking law came into effect in August 2014, it had an immediate impact. Restaurants cleared smoking areas from tables, owners put up no-smoking signs, and citizens adjusted to the idea that indoor spaces should be smoke-free. Enforcement was strong at the time, with the State Health Inspectorate (ISSH) issuing fines to violators.

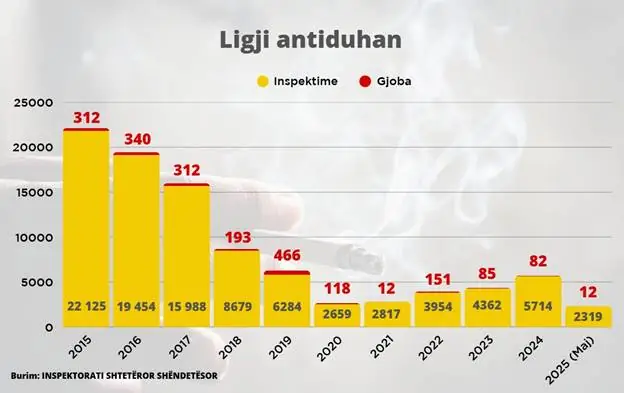

However, official figures show that this zeal did not last. According to data obtained by Faktoje, ISSH carried out 94,355 national inspections between 2015 and 2025. In 2015 alone, there were 22,125 inspections, while by May 2025, only 2,319 inspections had been conducted. Hence, a dramatic drop of around 90% over ten years. Compared to 2024, inspections also fell sharply, declining 74% from the 2015 peak.

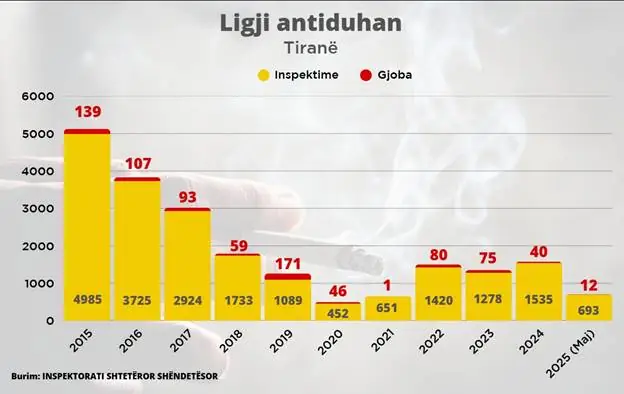

Tirana, the capital with the highest concentration of establishments, follows the same pattern. In 2015, 4,985 inspections were carried out, whereas in the first five months of 2025, only 693 were conducted, marking an 86% decline. The law, initially enforced rigorously, has gradually fallen into neglect, becoming almost nonexistent, especially over the past five years.

Beyond inspections, the situation with fines is equally concerning, reflecting the ineffective enforcement of the law. Over the past ten years, a total of 2,073 fines have been issued. The highest number was in 2019, following the expansion of no-smoking areas, when 466 fines were imposed, more than double the figures from the years before and after. Yet this was only a temporary peak. After 2019, fines dropped sharply. With just 12 issued in 2021 and the same number in the first five months of 2025.

Even more worrying is that fines, when issued, are rarely collected. Of more than 2,000 fines imposed over the past decade, only 262 were enforced, just 12.6%. The total collected amounted to 786 million Lek, while the rest remains tied up due to delays in enforcement.

Experts: Public health at risk

Roland Shuperka, one of the architects of the anti-smoking law, summarizes the problem: “In many public spaces, especially bars and cafes, the law is not implemented in practice.”

He lists several causes: lack of political will, insufficient real monitoring, unequal treatment of establishments, and paradoxically, excessively high fines that have opened the door for abuse by inspectors themselves.

Perhaps most crucially, there is no sustained awareness campaign. Initially, anti-smoking messages were displayed in every venue, school, and media outlet. Today, these messages have largely disappeared, creating space for the normalization of smoking in indoor environments.

“The law has served as a cornerstone for public health in Albania, but strong commitment to enforcement and oversight remains essential,” concludes Roland Shuperka, an expert on tobacco control in Albania.

The consequences are clear. Albania has one of the highest smoking rates in the region, with roughly 38% of the population smoking. Tobacco is the leading cause of seven types of cancer, including lung cancer (90%), laryngeal cancer (90%), pharyngeal and esophageal cancers (80%), cancers of the oral cavity and lips, and bladder cancer (70%).

Doctors warn that the growing number of young smokers will have catastrophic effects. By 2030, the incidence of cancer in the country is expected to rise by 60% compared to 2020, primarily due to tobacco use. Instead of awareness and prevention, young people are being exposed to a culture where cigarettes are perceived as a normal part of social life.

The history of the anti-smoking law in Albania reflects an initiative that began with enthusiasm but ended in failure. In 2014, it exemplified how the state could implement strong rules to protect public health. Ten years later, it demonstrates how the lack of political will, everyday petty corruption, and societal indifference can dismantle even the most important initiatives.

This article was prepared with the support of the “Friedrich Ebert” Foundation in Tirana.