His party emerged victorious in the early elections on December 17, 2023, but President Vučić couldn’t find peace due to protests challenging the results. Once again, he reverted to the narrative of the ‘external enemy,’ alleging that protests were incited by third parties such as Albania or the West, a claim reinforced by Russian diplomats. Experts deem this strategy an age-old tactic that showcases the difficulties within the Serbian president’s hold on power.

Jona Plumbi

This year has been defined by powerful anti-government protests in Serbia. It all started in May 2023 when protester crowds filled the streets of Belgrade in response to the shock caused by two consecutive mass murders. Initially, a 13-year-old boy shot and killed eight students – seven girls and one boy – along with a security guard at a school in the center of the capital, Belgrade.

Just a day after the school shootings, a 21-year-old opened fire on pedestrians from his vehicle in a rural area south of Belgrade, killing eight people and injuring 14 others.

The parents of 13-year-old Ema Kobiljski grieve during the funeral at the central cemetery in Belgrade, Serbia [Armin Durgut/AP Photo].

Following these events, a strike was organized by the teachers’ union of Serbia, calling for an end to the incitement of violence in the country.

The protests intensified into successive marches, with tens of thousands of participants calling for the removal of Vučić in what became known as the ‘Serbia against Violence‘ movement.

People marching during a demonstration against violence in Belgrade, Serbia, on Friday, May 12, 2023. (AP Photo/Darko Vojinovic)

The situation escalated even further with the Serbian government rejecting the demands of the protesters and the opposition’s hesitation to align with the movement, leading to a vote of confidence in the government. As a response, Vučić dissolved the government in November and declared early parliamentary elections in Serbia.

But, his troubles didn’t end there.

The election results announced Vučić’s party as the winner, and the streets were once again crowded with protesters claiming election theft.

Offense is the best defense

As the electoral campaign began and the opposition continued to contest the elections with ongoing protests, anti-Albanian and anti-Western narratives emerged in Serbia.

According to Vučić, the protests following the announcement of the election results were claimed to be supported by Albanians. Vučić’s statements were made for Serbian television at the end of the year, to be later shared in the Albanian language as well.

‘The opposition perhaps believes it can win some votes from the Albanians, or who knows why. They don’t only support independent Kosovo, but they’re also prominent Albanian lobbyists. Citizens of Serbia should be aware of this. 95 percent of those in the opposition are supported by Albanian lobbyists’, declared Vučić.

According to the Serbian president and his allies, another scapegoat for the opposition protests is the West and the European Union. Vučić raised allegations of external interference in the elections in Serbia, as well as in the protests that followed. The thesis is supported by the Russian ambassador in Serbia, Bocan Kharchenko, who stated that Vučić has indisputable information that the protests are incited by the West.

The narrative was reiterated by various officials, reaching its peak with accusations from the Russian Foreign Minister, Sergei Lavrov, of an attempted illegal seizure of power in Serbia.

What occurred in Belgrade is another attempt to orchestrate an illegal takeover of power.’, Lavrov stated for the Russian media.

In January 2024, Vučić reiterated his claim, stating to the media that the activity of ‘foreign actors’ in Serbia before and after the December 17 elections has been “more serious than ever before’. He has not specified on any occasion to whom he refers when talking about intervention and financing against Serbia.

The Russian narrative also deemed Serbia’s accusations of the EU’s involvement in the anti-government protests as part of the EU’s narrative, as stated by the spokesperson for the European Union, Peter Stano.

‘It is entirely incomprehensible to say that the European Union is trying to intervene or stimulate any kind of anti-government protests; these are Russian narratives that need to be addressed.’ – Stano said in a press conference. As of now, no one has been accused or arrested for election interference or attempting to overthrow the government in Serbia, leaving the statements from Serbia and Russia in the sphere of divisive anti-Western narratives, as well as against Albania.

Capitalizing on the danger from the ‘external enemy’

The narrative of intervention by Albanian lobbyists or Western governments is utilized by Vučić to mobilize the most fervent segment of his supporters. This is how the Researcher, Ermal Hasimja, presents the situation, who doubts that the Serbian public as a whole believes in these theses, at a time when dissatisfaction appears to be widespread.

In this way, Vučić also hopes to benefit from the effect of the threat of the “external enemy” just as Milosevic attempted to do over two decades earlier. – Ermal Hasimja, Researcher in political science and communication.

The Diplomat, Agim Nesho, shares the same opinion, bringing to mind previous instances when Vučić has used the same strategy.

‘Vučić always portrays himself as a victim and seeks an external enemy whenever a serious event occurs that he finds difficult to hide. The idea of Albanian lobbyists has been present in his rhetoric for years, depicting them as adversaries of Serbian interests and also of the international alliances that Serbia has with Russia, China, etc.’ – Agim Nesho, Former Ambassador of Albania to the UN.

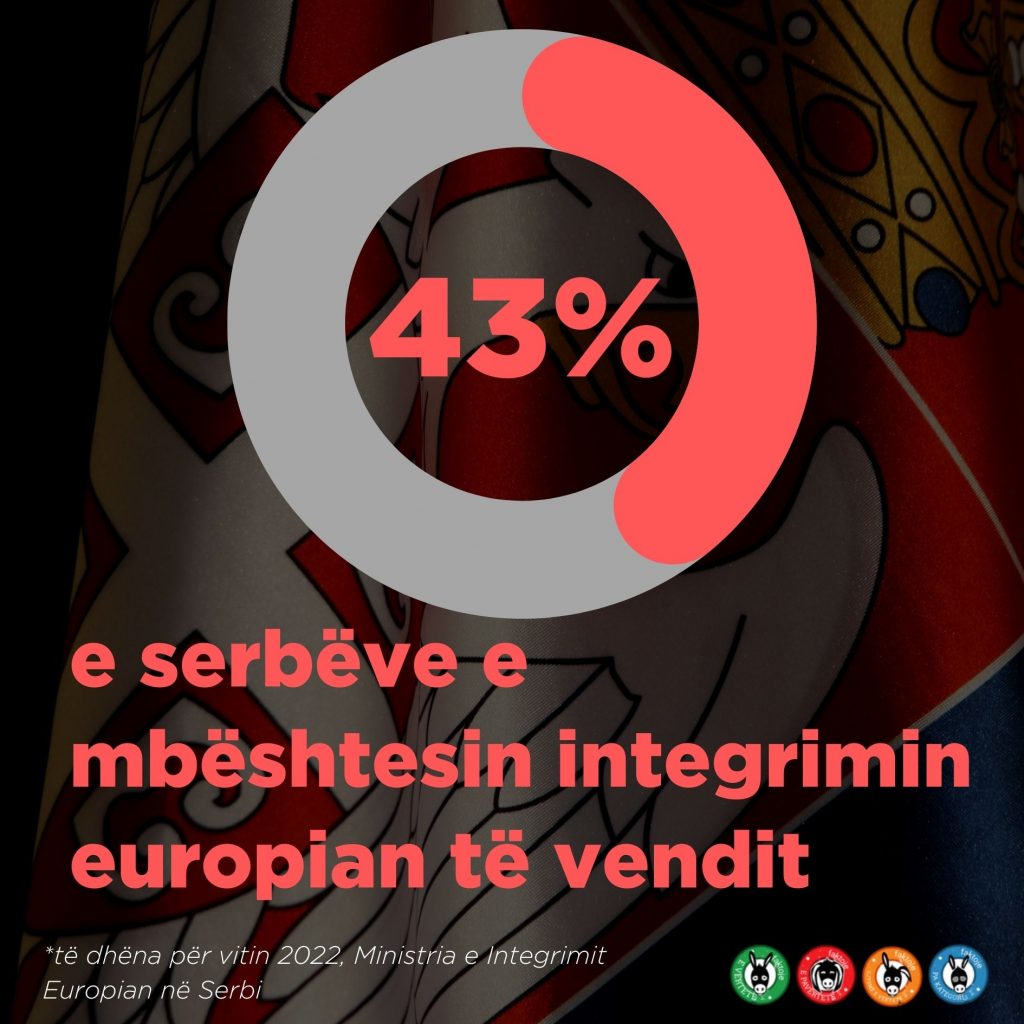

Public opinion in Serbia regarding support for European integration is the lowest in the region, with 43% of citizens in favor and 32% opposed, according to the latest statistics from the Serbian Ministry for European Integration.

It is precisely this high percentage of anti-Western sentiment that Vučić seeks to capitalize on, according to Ermal Hasimja, who sees Vučić’s effort aligned with Russian policies.

In terms of Russia’s objective, Diplomat Nesho argues that Russia needs Serbia and its nationalist policies as a precedent for advancing its policies in Euro-Asia‘.

Another advantage anticipated by Vučić from this chosen strategy, as per Ermal Hasa, is the pressure he applies to the European Union by leveraging the threat of closer ties with Russia.

On the other hand, Nesho points out that Russia’s accusations about the West funding and encouraging anti-government protests in Serbia aim to highlight two elements.

‘Firstly, because Serbia is [Russia’s] partner, and it will not tolerate destabilization of the regime in Belgrade. Secondly, because the West, in its projects in Eastern Europe, consistently engages in destabilizing initiatives against the interests of the people. Russia has stated that the West is promoting with the opposition in Belgrade what it did in Maidan Square in Kiev (2014). Fundamentally, Russia’s defense is aimed at guaranteeing autocratic regimes and their pro-Russian policies.’ – He argues.

The Researcher, Ermal Hasimja, believes that such strategies, on one hand, risk deepening the polarization of the Serbian public opinion, already divided between pro-Western and pro-Russian factions. It simultaneously highlights the challenging situation faced by Vučić’s government.

This writing has been produced as part of the regional initiative of the Center against Disinformation in Western Balkans.