By Jona Plumbi

The financing of political parties and election campaigns is one of the most important yet least regulated topics under Albanian law. The amount of money spent by political parties during campaigns is only made public one year after the electoral process has concluded, which diminishes the relevance and impact of any findings that may come from this audit.

The lack of transparency in the economic activities of political parties prevents citizens from understanding and assessing them based on the sources of their funding and the amount of money spent on campaigns. Furthermore, a non-functional penalty system makes the financial activities of political parties, particularly during elections, a complicated mess that is difficult to digest.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the inability of institutions to monitor and investigate political party financing, speculation on this issue is widespread.

New parties competing in the 2025 parliamentary elections have also joined this ‘battle.’

During a televised debate between the leader of the ‘Mundësia’ Party, Agron Shehaj, and the leader of the ‘Shqipëria Bëhet’ Initiative, Adriatik Lapaj, numerous accusations were made regarding the funding sources of the parties involved.

Shehaj accused Lapaj of benefiting money from his work as a lawyer for a company, the administrator of which was later investigated for involvement in a criminal organization.

On the other hand, Lapaj accused Shehaj of breaking the law by financing his party with his own money.

This situation, according to researcher Afrim Krasniqi, once again highlights the legal issue that Albania faces in setting standards for the transparency of political party finances.

The current system is based on trust and post-factum declarations, meaning that political actors report their electoral spending two months after the elections, and the Central Election Commission (CEC) only verifies their declarations and checks whether they align with the data obtained through the banking system. The entire system of informal donations from party members, lobbying groups, oligarchs, or other forms, such as in-kind donations, is not declared and cannot be verified by the CEC, said Afrim Krasniqi, researcher at ISP.

Shehaj stated that as of February 2025, his political party’s bank account still had 130,000 Euros, money that came from his personal funds, which he had deposited into the account.

Lapaj remarked that this is prohibited by law, as otherwise, any businessman could establish a personal party.

‘Did you know that the law prohibits this? So, you’re suggesting a political model where businessmen create business parties? The law does not allow this. There’s a penalty of 10 million Lek. The law allows up to 10 million Lek. It’s the law for political parties,’ said Adriatik Lapaj, leader of the ‘Shqipëria Bëhet’ Party.

For Agron Shehaj, these are lies.

What does the law and experts say?

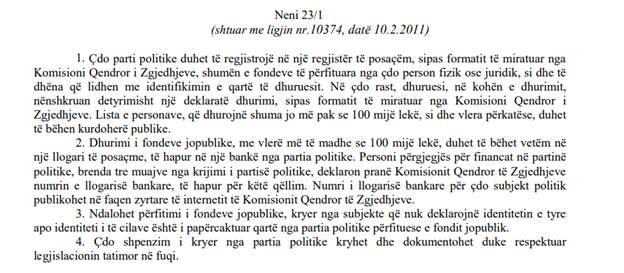

In fact, the law on political parties does not set a limit on the funds that can be donated to a political party, as long as they are declared in the prescribed formats and accounts.

Economist expert Zef Preçi explains that the Electoral Code, with its recent amendments, has established specific legal guidelines regarding the sources of campaign financing, but it does not provide specific provisions for periods outside of the campaign itself.

The only legal restriction on the amount of money that can be donated to a political party is specified in the Electoral Code, which states that ‘the amount that any natural or legal person may give to an electoral subject, including its candidates, cannot exceed 1 million Lek, or the equivalent in goods or services.’

However, this restriction only applies during the 4-month period leading up to the elections, which, in this particular case, begins on January 11, 2025.

If a violation occurs, the Electoral Code specifies that the offending party ‘will be penalized with a fine of up to 30 percent of the amount donated‘.

But if the money is deposited into the party’s bank account and spent before the 4-month campaign period, such as for establishing party branches, the law does not prohibit this.

On the other hand, since January 11, which marks the start of the 4-month period before elections, the ‘Shqipëria Bëhet’ party, led by Adriatik Lapaj, has declared 784.8 Euros in donations on its website.

For donations exceeding 100,000 Lek, where the donation date is not provided, ‘Shqipëria Bëhet’ reports a total of 1,932,700 Lek in donations and 1,246,234.86 Lek in-kind donations for meetings with the diaspora.

The legal framework requires transparency in party finances at all times, but this requirement is not being met by the new parties.

Moreover, the legal framework ensures a high level of transparency, requiring the electoral entity to ‘…make public and provide full and uninterrupted access for third parties to the database where it records donations, loans, or credits received by the entity and its candidates, for all amounts equal to or exceeding 50,000 Lek’ (Article 92/1, point 6),’ explains Zef Preçi.

Despite these legal provisions and restrictions, Zef Preçi considers them largely formal.

Even though these regulations were established with top-tier Western assistance, their implementation remains largely superficial. The influx of money from public funds, private businesses, and criminal activities both inside and outside the country is a widespread phenomenon, now becoming increasingly visible in the current electoral period – Zef Preçi.

The Central Election Commission (CEC) is responsible for auditing campaign finances, a process that is typically completed about a year after the elections. However, Afrim Krasniqi argues that this audit is not only delayed but also insufficient.

The current system relies on trust and post-election declarations, meaning that political actors report their campaign expenses two months after the elections. The CEC then verifies only these declarations and their alignment with data obtained through the banking system. However, informal donations—whether from party members, lobbying groups, oligarchs, or in-kind contributions—are neither declared nor subject to verification by the CEC, he explains.

Alternative Approaches to Financial Oversight

Afrim Krasniqi suggests that Albania should have adopted regional best practices, such as Kosovo’s model, where financial disclosures must be submitted before election day. This allows voters to assess political actors not only based on their platforms but also on their financial transparency and adherence to legal spending limits set by the Electoral Code.

At a minimum, key political figures could follow the example of Giorgia Meloni in Italy, where political parties publicly report their daily activities and expenses. In Albania, such transparency should at least be required for public events. Additionally, the media and civil society monitors should be granted access to oversee campaign financing—a practice that, so far, has not been implemented, Krasniqi argues.

The Ineffectiveness of Financial Penalties Regarding penalties for violations of campaign finance rules, both Afrim Krasniqi and Zef Preçi believe they have little impact.

In the last local elections, several mayors and candidates were fined by the CEC for irregular financial declarations, but these sanctions had no political consequences. This suggests that candidates are willing to pay the fines as long as they secure their mandates and benefit financially from their political positions,’ Krasniqi explains.

The legal framework for penalizing violations of political party financing is ineffective. The fines imposed are relatively small—disproportionate to the damage caused by these violations—and do not address the potential distortion of voter choice. In other words, these sanctions do not include the possibility of revoking the mandate of a party or candidate who has secured victory through illegal financing,’ – concludes Zef Preçi.

Based on this assessment, the statement by Adriatik Lapaj, leader of the ‘Shqipëria Bëhet’ party, is rated as partially true.