The system of rules that allows political parties to conduct electoral campaigns under fair conditions has been shaken by the increasing involvement of social media. The lack of rules that would enable fair competition in the digital sphere has led to the use of various tactics by political parties and candidates, aiming to influence citizens’ perceptions and, ultimately, how they vote. The local elections of May 14 2023 in Albania showed that in the upcoming parliamentary debate on electoral reform, important considerations should also include provisions for regulating electoral campaigns on social networks.

Jona Plumbi

The utilization of social media in electoral campaigns is on the rise in each election process. This trend is fuelled by the convenience offered by the digital realm. On one hand, political parties can effectively reach out to a larger number of citizens in a shorter period and at a lower cost. On the other hand, voters now have more opportunities to access information about candidates from their phones or computers.

The advancements of digital technology have not been matched by updates in regulations and laws that outline its democratic usage, particularly during electoral processes. International organizations like the Venice Commission and OSCE-ODIHR have made efforts to establish certain principles and general guidelines. However, beyond these standards, countries like Albania engage in electoral campaigns amidst digital anarchy.

At a time the country, institutions, and especially voters are far from being prepared to deal with the electoral campaign in the digital realm, lacking mechanisms to control and categorize information, the political parties have already developed well-established strategies and practices to influence citizens’ perceptions and, ultimately, their votes.

Electoral campaign in the digital era.

Based on the leading role that social media has taken in electoral campaigns, the Venice Commission, in December 2020 adopted some basic principles for the use of digital technology in democratic electoral processes. Among other things, the Venice Commission emphasizes the threat posed to society by new forms of crime enabled by the digital realm, such as the processing of personal data or the ‘deliberate shaping of social interaction with selective (and sometimes strategic) information for users, fostering a biased understanding of reality and impede freedom of expression within society[1].”

The involvement of other actors in electoral campaigns, such as civil society organizations, individuals, and even online media, has now become a significant factor in the outcome of elections due to the possibility of purchasing advertisements on social networks. The Venice Commission specifies that ‘these actors are allowed by social media to operate seemingly independently of the official campaign of a political entity and even work beyond national “barriers.

The Venice Commission emphasizes the significance of transparency and accountability when it comes to the placement, costs, and responsibility of advertisements on social media during electoral campaigns. This ensures that citizens are well-informed about the context in which these elections are conducted. Lutfi Dervishi, a lecturer in investigative journalism at the University of Tirana, envisions the future of elections closely connected to social media. “There is a shift in focus, finances, and attention from traditional methods to modern ones. This represents the future, and technology always precedes legislation.” – he says, highlighting that every politician would prefer to have analytical data on the reach and popularity of their content among the public.

How electoral campaigns are sponsored on social media

In the realm of electoral advertising, there are emerging actors like anonymous profiles and online media with unknown ownership. This anonymity enables political parties to engage in unofficial campaigns, exploiting the absence of regulations. By unofficially funding online media, they seek to exert a more significant influence during the campaign

The most common and official form of sponsorship is through paid advertisements by political parties or the candidates themselves. Another method is proxy sponsorship – where a third party is involved. These third-party actors are not directly engaged in the electoral campaign but sponsor news or political propaganda during the campaign without disclosing the source of funding for these purchases or donations to the supported party.

Sponsorship by political parties

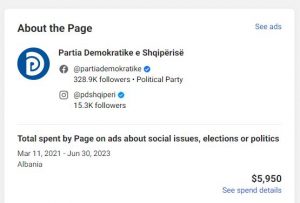

To understand how and how much political parties sponsor on social networks during the electoral campaign of the local elections in May 2023, Faktoje conducted an observation through the Facebook and Instagram ad library. Through the Meta Ad Library anyone can check how many ads a page has sponsored and how much money has been spent on them on the two Meta platforms.

From this register, the total expenses made for advertisements can be approximately calculated. For example, the Socialist Party has sponsored 80,000$ worth of ads in the last two years (March 2021 – June 2023), averaging 40,000$ per year.

In addition, the Democratic Party spent approximately $6,000 during the same period. The Coalition for Reforms, Integration, and Consolidated Institutions (KRIIK), monitored the expenses of political entities on Facebook and Instagram from the announcement of the election date (October 24) until the election day (May 14). The expenses for advertisements of the two main political subjects were reported to be almost equal, with around $48,000 spent on “Bashkë Fitojmë” (Together We Win) and about $44,000 on the Socialist Party.

Candidate Sponsorship

The expense figures from political parties do not give a complete picture of the money spent by each party. A significant portion of social media ads is sponsored by the candidates themselves during the elections.

Research in Meta’s ad library reveals that the expenses of the two main candidates for the largest municipality in the country, Tirana, are nearly identical, despite occurring during different time periods.

According to this data, the SP candidate, Erion Veliaj spent approximately $19,000 during the campaign month. On the other hand, the opposition candidate, Belind Këlliçi spent about $8,000 during the same period. The difference is that Këlliçi started advertising for the Tirana Municipality race long before the official campaign began on April 14. If we calculate Këlliçi’s expenses for electoral ads from November 2022, their total value exceeds $15,000.

Lutfi Dervishi, a lecturer in investigative journalism at the University of Tirana, emphasizes that political parties and candidates should declare these funds spent on social media sponsorships. “Normally, every election expense is declared, and the audit should verify how these funds have been utilized during the electoral campaign” – highlighted Dervishi for Faktoje.

Sponsorship by External Parties

Another way that political parties use for advertising on social media is through other actors. These are all actors involved in electoral campaigns supporting a party or candidate without being directly part of the electoral process. Examples of other parties advertising on social media in Albania include fake profiles, online media, and well-known personalities (influencers).

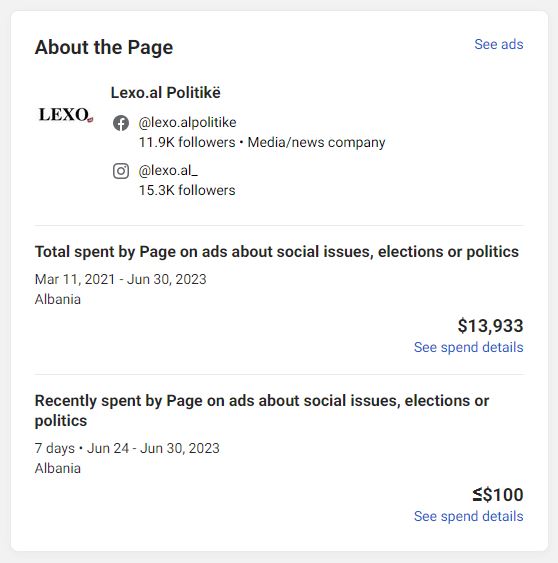

In the latest elections in Albania, Faktoje’s investigation identified several online media that sponsored electoral advertisements. Propagandistic content and biased information were presented as editorial content and advertised on the network without declaring the source of funding.

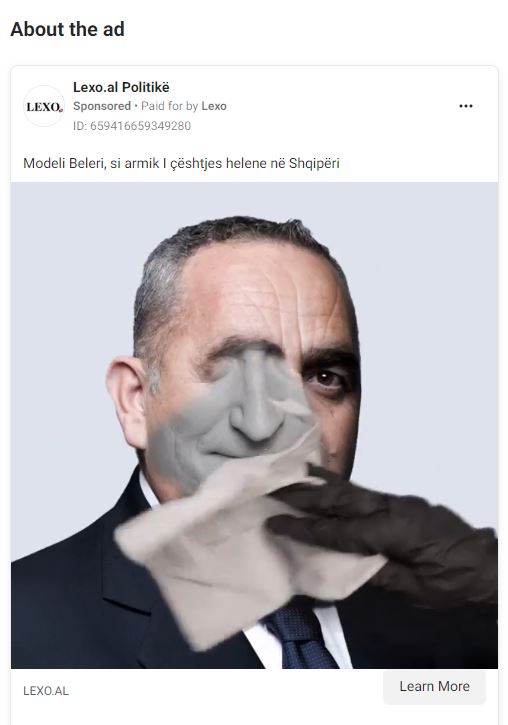

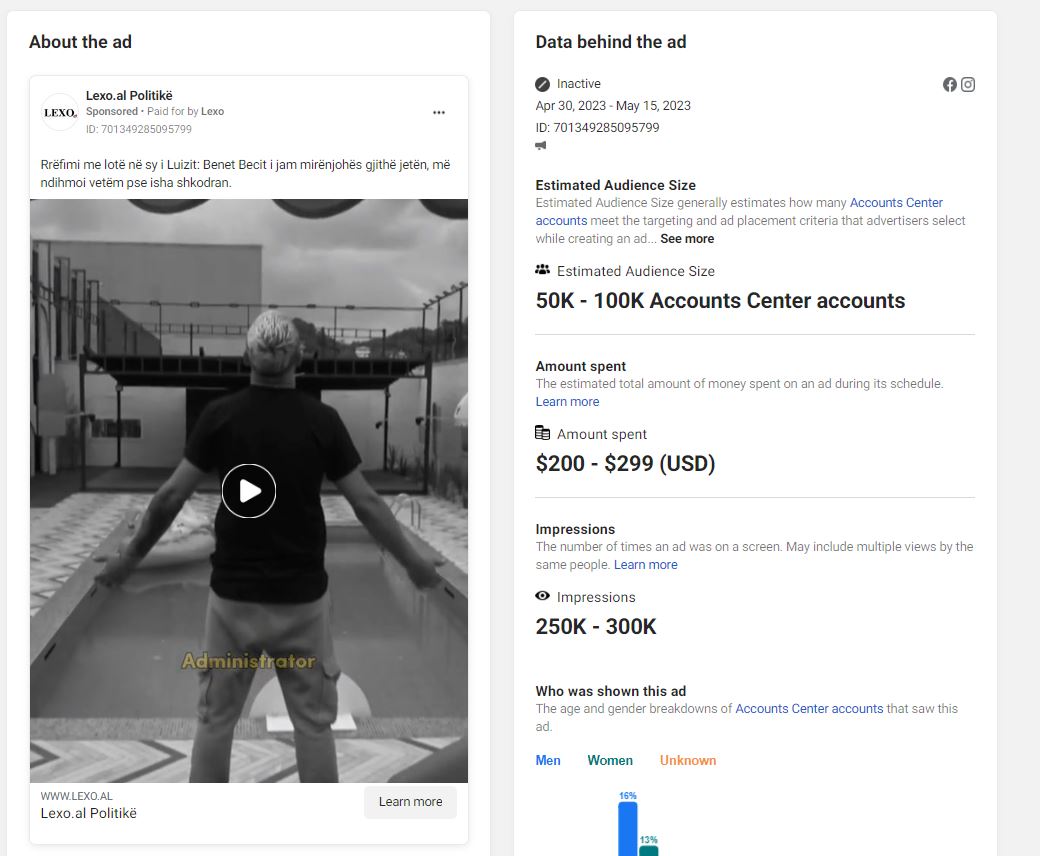

The online media “Lexo.al Politikë” in Meta’s ad library shows that it spent nearly $14,000 on political ads over the course of two years, which is recorded as self-expenditure, without another financier behind it. One of these ads was the Socialist Party’s electoral spot for Himara Municipality

This case demonstrates how funds spent on advertisements favour political parties during campaigns without being registered as financial donations or informing the audience that the ads are paid for by the Socialist Party itself.

The situation becomes even more problematic when the message is more disguised.

Such was the case of the involvement of a television show in an electoral campaign. In a widely followed program (reality show) on national television, a key character in the show expressed support for a mayoral candidate. Using his personal life events, this character ‘painted’ the electoral candidate as his saviour, conveying this message to all his supporters in the show and influencing their perception of the candidate. Later, this message was sponsored as an ad on social media by “Lexo.al Politikë” for two consecutive weeks.

Lutfi Dervishi, a lecturer in investigative journalism, sees the impact of social media on politics from different angles. On one hand, social media becomes a battlefield for “games” involving users’ emotions. On the other hand, social media has become a political influencing factor.

“People make decisions based on emotions and then use logic to justify their decisions. Even in politics, where emotions are highly involved, undoubtedly, social media has a significant impact. Furthermore, we have the inevitable influence of technology on political decision-making. If people’s focus is more on the small screen [social media] than on the big screen [television], it means that social media has influence,” he argues.

The ‘unseen’ Campaigns on the Network

Ad placements on social media during elections have hidden forms beyond those directly sponsored by the platforms themselves. These forms include ads by so-called influencers, web ‘trading’, and existing profiles.

Influencer Sponsorship

In the realm of social media, influencers are well-known personalities who influence their followers’ perceptions. During electoral processes, it becomes essential to differentiate between content produced as “organic” and content used for advertising purposes, as the line between the two is often blurry.

While organic content is protected by freedom of expression and should only be regulated in exceptional cases, content for advertising purposes may be subject to transparency standards according to international norms – OSCE-ODIHR

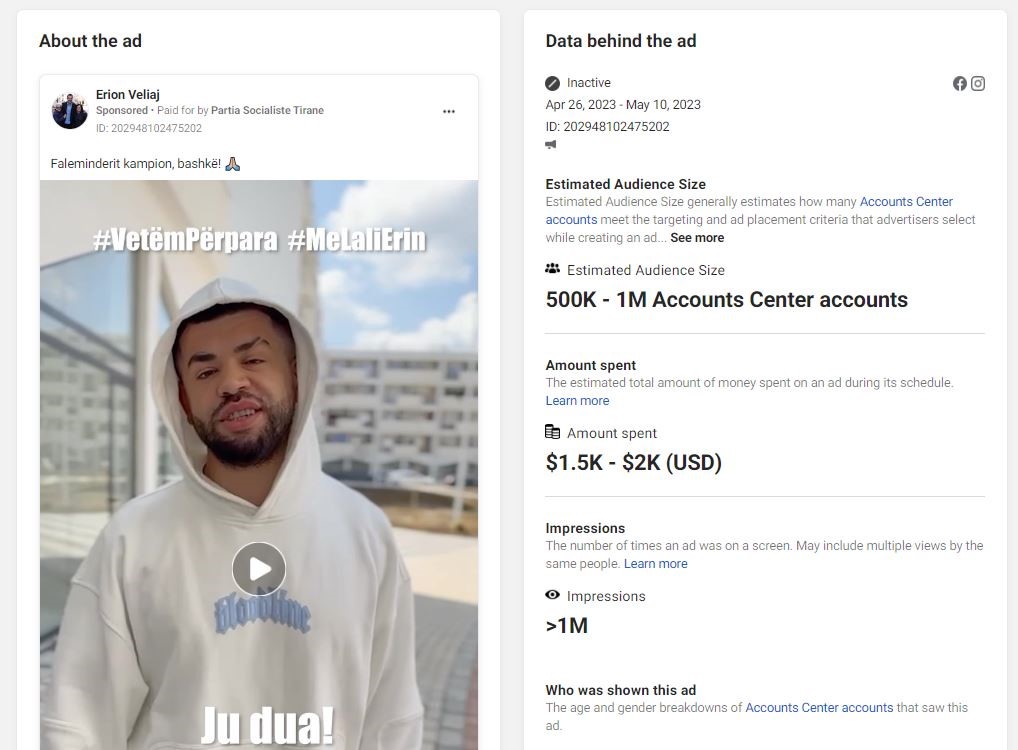

In the May 14, 2023 elections, the candidate who applied this advertising method in the form of a “campaign within the campaign” was the Socialist candidate for Tirana, Erion Veliaj. Seventeen VIPs, some standing side by side with the candidate, and others from a distance, expressed their support and wished him victory in a video.€5,000 – €7,000 is the minimum amount of money [2] that Erion Veliaj spent to spread supportive messages from various campaign figures on the network e. Erion Veliaj’s “champion” was the singer Noizy, whose message was sponsored with €1,500 – €2,000, exceeding the amount spent on distributing Rita Ora’s message.

However, while Facebook’s ad library allows us to see how much Veliaj spent on distributing these videos on the network, what is not known is how much each of these VIPs was paid for delivering the chosen message.

“Buying-Selling” with well-known pages during campaigns

The propaganda of party theses during electoral periods is also carried out through Facebook pages that engage only during the campaign. By using pages with a stable number of followers, parties or candidates manage to convey their propaganda as if it were the page’s own content.

The difference becomes quite noticeable, especially on pages that consistently support a particular political stance or force and engage in defending opposing theses during the campaign. At the end of the campaign, this commitment diminishes. An example of this practice in the May 14, 2023 elections was the page known as “Brryli Broadway.” This page, perceived as oppositional in the public eye and mostly followed by citizens with the same ideological mindset, continuously attacked one of the opposition candidates for mayor during the electoral month campaign.

Based on Faktoje’s observation, comparing periods before, during, and after the elections, it becomes evident that this page carried out an extensive campaign in support of the majority candidate for mayor in Elbasan. In quantitative terms, at least one month before the electoral campaign, this page had not published any content related to the Elbasan municipality candidates. However, once the electoral campaign started, from April 19 to May 14, in less than 30 days, Brryli Broadway made 30 publications, all of which attacked the opposition candidate in Elbasan. After the elections and up to two months later, the page made only 5 additional posts on the same topic

According to OSCE guidelines on election monitoring, such pages “need to be subject to some analysis and be assessed, particularly to see whether they disseminate harmful or manipulative content”.

“The “Recycling” of Groups

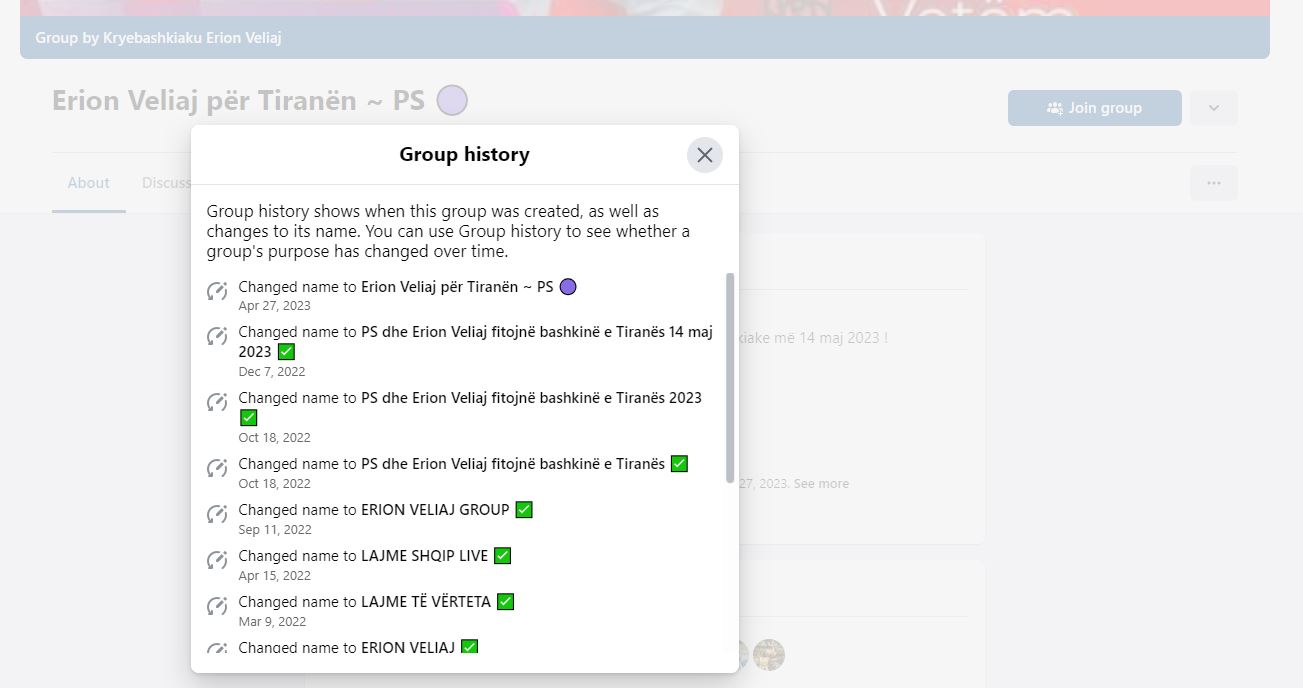

The social network Facebook has created several spaces for organizing its users. In addition to profiles and pages, Facebook also allows the creation of discussion groups where members discuss and share information with each other. Even this communication space has not escaped the “vortex” of the electoral campaign.

What such groups often do is that, once they reach a desired number of members or once electoral periods approach, they change their name and the content distributed within the group to influence their members.

Online Use of Administration

The findings of OSCE-ODIHR for the elections in Albania, including in the preliminary report on the May 14 elections, mention the use and pressure on the administration as one of the most apparent problems of the electoral process. However, while this happens within the existing legal framework, the complete absence of laws or rules governing the use of digital technology in elections has led to various forms of using the administration in elections, ranging from the simplest to the most organized ones.

Commissioner’s Decision on Social Network Posts

In the middle of the electoral campaign, the Commissioner for Elections, Ilirjan Celibashi, ordered the prohibition of reposting on institutions’ websites of activities covered on the personal profiles of the public institution’s leaders, if these profiles are considered personal.

The decision, the first of its kind to ‘regulate’ the social media campaign, came after complaints made to the CEC by the Helsinki Committee and opposition MP Albana Vokshi

The initial allegations accused the Local Office of Pre-University Education in Korçë of asking the teaching staff to report the number of followers and reposts of this institution, as well as the Ministry of Education and Sports. The Central Election Commission concluded that “on the official ‘Facebook’ pages of some institutions under the administration of the Korçë-Pustec Local Government Unit and other educational institutions, clear promotion of political subjects is observed in the local elections of May 14, 2023.”

The Activ1st App and “Herd Mentality”

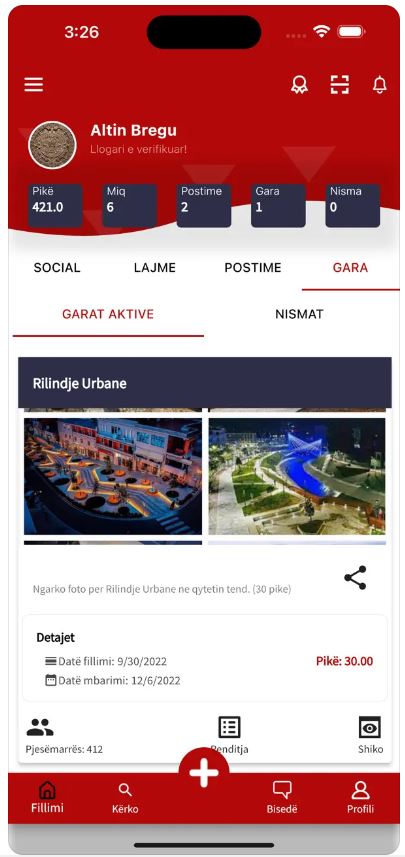

A novelty in the 2023 local elections was the use for the first time of an app created by the ruling party, but denounced by citizens, journalists, and civil society as a control tool over the administration to use it for propaganda

The app can be downloaded by anyone, but after registering with several personal data, Activ1st notifies you that the “account is pending verification.” If you are not a public administration employee, the application does not verify the account, making it impossible to see how it works. Based on the images published by the application itself, it is understood that each personal account is evaluated with points. At the same time, the primary data that this application processes for each account are the number of friends, the number of posts made, and the number of competitions or initiatives taken by each.

The app’s description on the pages where it can be downloaded explains the scoring system.

“Activ1st relies on a scoring system that interacts with the online platform, translating it into an assessment reflected on the “leaderboard,” according to which individuals who show more initiative will be evaluated.” In short, being active on the online platform translates into points and consequently into an assessment of the administration employee.

In the images uploaded by the application on the network, we can see how competitions are conducted within the app. During the period from September 2022 to December 2022, it seems that the evaluation of administrative employees was also based on the number of photos they uploaded online for “Rilindja Urbane” (Urban Renaissance).

The Venice Commission evaluates that the organization of such accounts, which increase the massive dissemination of specific information, with the aim of creating streams of public opinion and artificially influencing the acceptance or rejection of people and ideas, creates false impressions for social media users. By creating widespread support, a domino effect is generated, where people accept ideas because they are accepted by the apparent majority. “This – emphasizes the Venice Commission – through which individuals neglect personal responsibility and submit to the will of the collective[3]”.

Another problem that arises from this form of organized use of social networks is the influence it has on Facebook’s algorithms. “By having hundreds of thousands of organized likes on Facebook, the algorithm ‘promotes’ this publication more organically, without the need to pay for higher visibility,” explains Dervishi.

Sponsorship of Non-Candidate Work

False perceptions were also created on the network during the May 14, 2023 elections through the promotion of work that was carried out with funding and oversight from foreign donors, in addition to the obligatory sharing and liking of posts on social networks

One of the most prominent examples was the use of schools rebuilt by the European Union after the 2019 earthquake for the electoral campaigns of mayoral candidates. Some incumbent mayors seeking re-election from the Socialist Party were involved in this “show.” Out of the 9 municipalities that benefited from the EU’s program for the reconstruction of educational infrastructure after the 2019 earthquake, five incumbent mayors utilized the work funded and supervised by the EU for their election campaigns.

In Conclusion

The integration of digital technology and, specifically, social networks into election campaigns has “disrupted” the balance between regulatory legal frameworks and reality. While the number of actors engaged in digital campaigns has significantly increased in the shadow, the methods for maximizing influence on social media users have become more sophisticated over the years. However, the same level of sophistication does not apply to the legal framework needed to establish rules in this new domain.

While the State Commissioner for Elections took the initial step towards addressing injustices in the realm of social networks during the local elections on May 14, the parliament must now prioritize the new reality of implementing election campaigns on social networks as part of the electoral reform commission. Failure to do so would result in a skewed perspective, focusing solely on the time and money invested in monitoring and implementing laws for “traditional” campaigns.

[1] Venice Commission, Principles for the Use of Digital Technologies in Electoral Processes in line with the fundamental rights, II,A,2020

[2] The count includes only ads with a defined budget. Six ads sponsored with less than $100 each are not included in the mentioned total.

[3] Venice Commission – Principles for the Use of Digital Technologies in Electoral Processes in line with the fundamental rights, p.8